Fekete Anna – Benkei-Kovács Balázs: Image and Prestige – Cultural Places for the Youth: a Research on Attendance trends, decrease in use and the possibility of rediscovery

Cikk letöltése: pdf2020-10-21

The following research was carried out under the scientific research program of the National Institute for Community Culture of Hungary (NMI), in the academic year 2019/2020.

1. Introduction

The aim of my study is to measure the reputation and attendance of youth cultural centres in Hungary. This helps us to understand the reasons why young people choose other establishments to spend their leisure time in, and what needs youth centres should fulfil to be more appealing for them. Our aim is to identify these needs and to find the answers how the youth could find these institutions more appealing for participation and attending, thus becoming more active in their communities?

The situation of the young population in Hungary

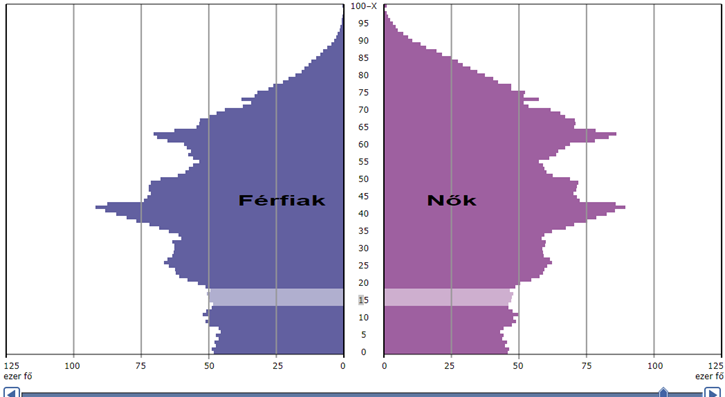

In Hungary’s case we can talk about an ageing society which means that the number of young people has been decreasing over decades. On the first graph we can see data from 2020: the population pyramid shows that there are more old people in the country than young ones. The first bigger protrusion can be seen between the ages of 35 and 45 and the second one between 60 and 70. The proportion of people under 20 years is very little compering to the others.

Figure 1.: Population of Hungary, classed up to genders and ages

January 2020.01.

(Source: Interactive population tree of Hungarian Statistics (KSH) korfa (https://www.ksh.hu/interaktiv/korfak/orszag.html))

Free time usage of the youth

The book Hungarian Youth Research 2016 (Margón kívül - magyar ifjúságkutatás 2016) emphasises that in the last years young people tend to favour watching TV, using the internet and spending time with their friends in their leisure time. It is important that the improvement of technology has a dual effect on personal relationships. It can help keeping in touch easier but at the same time this is a reason why young people do not meet each other personally so often, because they can communicate online as well.

The youth like to spend their free time with their friends and it is pretty common that they only hang out which means they do not do anything particular just choose being together and spending time together. This is not necessarily a bad phenomenon, youth centres should look at it as a new possibility to reach out for young people. (Csatari 2015.)

The relation between community culture and the youth

In the study Youth 2008 – Quick Results (Ifjúság 2008 Gyorsjelentés) from Béla Bauer and Andrea Szabó highlight that young people do not really visit the institutions of community culture. They rather go to other places or just simply stay at home. Another study, Hungarian Youth (Magyar Ifjúság 2012), four years later shows an even worse tendency. 24% of the youth admit that they do not have a group of friends regularly hang out with, this rate was only 13% in 2008. The study of Ádám Nagy (2016) confirms that this tendency still has not reversed.

The institutions of the youth community place in the cultural law

In Hungary the law CXL. 1997 on the museums, libraries and community cultural institutions differentiates the following types of cultural institutions: community house, cultural community place, community centre, cultural centre, multifunctional community cultural institution, folk high school, creative folk art house, youth house and leisure time centre.

The institution of youth community place belongs to that list, with special focus on the group of youngsters. “The youth community place is defined as an open community cultural institution, which is always in the service of the needs of the young population, giving them opportunity to create their own active communities. (Szabó - Kovács - Bitter - Bauer 2001: 91.)

2. International outlook – youth community centres and houses abroad

The institution of youth community houses and centres has been considered a popular one in the democratic countries of the Anglo-Saxon world: those venues are providing cultural-community services, apolitical offerings for youngsters, which are beneficial for strengthening the social network of the given countries, from the United Kingdom to Australia. The institutional form varies from Youth Community Centers [1] (Australia), to the Canadian Youth Centres [2] or to the Irish network of Youth Cafes [3] just to name a few. These models are similar to a franchise network: the youth community centres are offering similar programs and services in the different towns, following a national model, sometimes they operate 3 or 4 institutions in a bigger city, offering a geographic accessibility to the young residents.

In the United Kingdom, this initiative is often based on enhancing voluntary activities: For example the Youth & Community Centre [4], located in London’s Lewisham district, under the leadership of young people, giving labour opportunity for 50 people, and organizing programs for over 5000 attendees in a year. This kind of institution is specialised for big cities, a fresh initiative, founded in 2016, and became popular very quickly. (Source: https://www.youthfirst.org.uk/).

In Hungary, we have gained some knowledge already in the topic of the Youth Café of Ireland, presented partially earlier by Csatári (2015). Csatári underlines, that this type of institution receives the strong support of the Ministry of Youth, which even elaborated a methodological guideline in 2010 for making the activities of this youth centres even more effective. She summarizes the mission the following way: “The Youth Café is a safe and quality meeting point for youth serving the age-group of 10-25. A special place, operated by young people for young people”, in partnership with adults. A meeting point suitable for relaxing, safe, friendly, integrative gatherings and tolerant climate, for youth of both gender, and of different social backgrounds, that encourages building relationships with each other, with adults, without alcohol or drugs “ (Csatári 2015:9.)

The Youth Café has the following principles: 1. assuring the attendance of young people; 2. safe and quality place; 3. clear goals; 4. integrative atmosphere, and available for all the youth; 5. generating contacts and the building and developing of relationships; 6 supporting volunteerism and involving the youth into the organization’s activities and leadership;7.respecting the value of individual personalities;8. building on the strength of young people; 9. sustainability (Forkan-Canavan et al ii 2010).

The spread of the institution of the Youth Café dates back to the previous 2 decades: in 2000, there was only one institution of that type; and in 2013 163 Youth Cafés were registered across Ireland. (Forkan - Brady 2015). In the capital, and in Cork, the second most influential city, the number of them reaches 20-21, but altogether this institution is available in 26 cities in the country. (Idem.)

The literature differentiates 2 types for the clusterisation of that institution: the first one is related to the functionality of the cafés, the second one is based on the ownership of these institutions. (Csatári, 2015. Forkan-Canavan et al ii 2010. Forkan - Brady 2015)

Based on the functionality we can divide them into 3 groups: “1. The first type of youth café is simply a safe meeting place where young people can hang out with their friends, chat, drink coffee or soft drinks, watch TV or movies, or surf the Internet. 2. The second type of youth café includes all of the things offered above plus a variety of recreational and educational activities, chosen by the young people themselves, plus information on state and local services of interest to young people.3. The third type of youth café is the most developed and usually takes a few years to reach this stage. In this kind of café, all the things on offer above in Types 1 and 2 are available, plus a range of specific services, directly designed for young people. These might include, for example, education and training, healthcare information.” Forkan-Canavan et al ii 2010, 3.

If we are taking in consideration the division induced by the ownership, we can state, that the more spread are the independent (31%) and in the second lines are the state owned (Foroige), and those who are offering also work opportunity for youngsters (Youth work Ireland) (30-30%) (Forkan - Brady 2015) The family assistance centres and the catholic youth services are participating in that movement, with a more modest percentage (3-7%)

The first important finding of the international outlook underlines, that in the western European democracy, the youth community institutions are working in diverse forms, and within national networks. The second important thing to remark is that those institution are relatively newly founded ones also in that countries, and have undergone a rapid development in recent decades, which is illustrated by the 4 years of experience of the English example, and the 15 years of spreading of the Irish model.

3. The empirical research

3.1. The research questions and methods

We tried to make the investigation for answering the following questions:

- Have you already heard about the institution of Youth Community Spaces?

- Why is that this institution is not more popular?

- How could young people be attracted e into those youth community spaces?

The first step of the research was to realise a field visit and write a case study on a Youth community space, which is called Offline Center. The second step was the mediation and in a later phase also analysis of 2 focus groups interview. Based on those qualitative research phases, the tool of the quantitative survey was developed, which was shared within the young population aged between 14 and 30 years, reaching finally 254 respondents.

Focus groups

In the two focus groups we talked about the following topics: belonging to a community, attendance of different cultural establishments, use of free time, and of social media and marketing, youth centres.

The members of the two focus groups were open to the issue of participating in community culture, they were not passive and felt needing culture in their lives. „I visit a lot of cultural institutions. I go often to theatre, I have a season ticket, and I am very happy about it. I like to participate at literature evenings as well, in the Várkert bazár (A place in Buda Castle’s cultural district), at least one time in a month. And I am often attending a program offered by writer clubs. I appreciate those very much.” This was pretty surprising, showing obvious interest for the literature, because the researcher expected less attendance of cultural establishments.

Nevertheless, the finding was that none of the participants was a regular visitor of any youth community place / centre. Most of them had not even heard of them before and those who had, did not know their exact functions, tasks and the way of working. The mostly visited places preferred were where they can consume something such as restaurants, coffees, bars, malls and parks.

Still, youth centres may provide free of charge possibilities for recreation or simply a place for young people to gather, but they do not really know about these.

Research based on surveying method

Based on the former information we had set up an on-line questionnaire. IN the following chapter we are going to present the results of the 254 responses.. The data of the investigation were collected on-line, with Google survey tool, and we used simple random sampling for choosing the respondents.

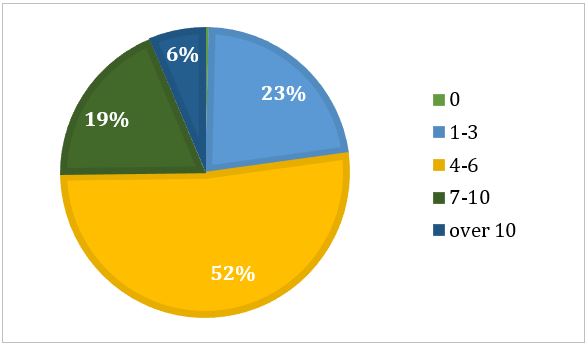

More than half of the answers indicate that they feel belonging to 4-6 communities. There were some people who stated belonging to less and some to a lot more, but 4-6 is the most common figure. These involvements are rather based on friends, hobbies, sports and religions but school constitutions and families also belong here. These data confirms the same results different youth studies have found.

Figure 2.: Number of communities attended / participant in the research

(Source: own empirical findings, June 2020.)

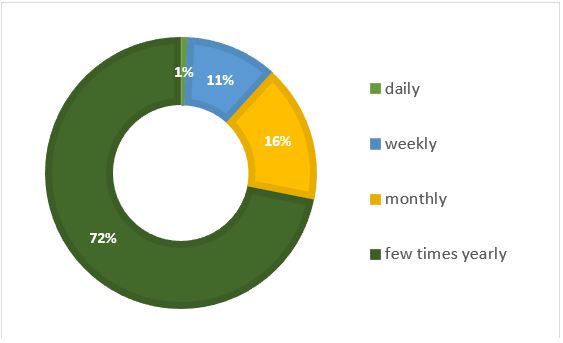

It is an important outcome that 52 percent, so more than half of the respondents has already heard of youth centres (132 people). Of course we do not know how much this means in terms of real knowledge about the institution but it is definitely some positive data. It is also surprising that 50,4 percent claims having already been to a youth centre but this also could mean only one occasion and regular visits as well.

Those who have been to a youth centre before, in most of the cases they heard about them from acquaintances (67,2%), from Facebook (60,2%), from Instagram (32,8%) and from their web-page (16,4%). It can be seen that apart from personal relationships it is the internet that can forward these information easily.

Figure 3. Frequency of attendance (Youth community places)

(Source: own empirical findings, June 2020.)

Those who have not been to a youth centre before (126 people) have been asked why they have never been to these institutions. 61,1 percent of them answered that because they had not heard of them before and 32,5 percent of them thought it was strange to simply go there. 23 people (18,3%) answered they were not interested in these kind of places and 20 people (15,9%) did not think they are for their age group.

75,4 percent of them answered, that good community, 68,3 percent of them answered that good programs could make youth centres attractive. 30 people (23,2%) answered good marketing, 29 people (23%) answered modern surroundings could be attractive to them, and 8 people (6,3%) think nothing could make them attend youth centres.

4. Summary

The results of the research are mostly reinforcing the findings presented earlier in the literature. The Hungarian youngsters are voluntarily organize themselves into communities in their leisure time, but the time spent together are linked less often to visiting community institutions.

It would be an important step for the development to make those institutions more popular: not only attracting the young participants, but keeping them as regular attendees, and enhancing their active membership of community.

The international examples show (United Kingdom, Ireland), that it is possible with a dedicated commitment to build up a strong network for youth population, even within a short period that may serve as a a model of best practice.

The empirical findings were matching with the results of the literature review. The level of public knowledge on the youth community places is giving us good hope. That publicity combined with strengthening voluntary activities, based on the model of an operating best practice, could be the basic ingredients for a successful development for the forthcoming period.

Literature:

- Bauer Béla, Szabó Andrea (2009): Ifjúság 2008 Gyorsjelentés. Budapest, a Szociálpolitikai és Munkaügyi Intézet. 149.p.

- Csatári Emese (2015): A fiatalok szabadidő eltöltési szokásaihoz alkalmazkodó ifjúsági közösségi tér – a hang out másik oldala. In- Párbeszéd: Szociális munka folyóirat, 3. évfolyam 4. szám https://ojs.lib.unideb.hu/parbeszed/article/view/5906

- Forkan, C., Brady, B., Moran, L., Coen, L. (2015): An operational profile and exploration of the perceived benefits of the youth cafe model in Ireland. Dublin, Department of Children and Youth Affairs. 99 p.

- Forkan, C., Canavan, J., Devaney, C. and Dolan, P. (2010): Youth Cafe toolkit 2010. The Office of the Minister for Children and Youth Affairs. Dublin: The Stationary Office. Minister for Children and Youth Affairs.

- Nagy Ádám (2016): Margón kívül – magyar ifjúságkutatás 2016. Budapest, Excenter Kutatóközpont. 408. p.

- Szabó Andrea, Kovács Szilvia, Bitter Brunó, Bauer Béla (2001): Gyermek-, művelődési és ifjúsági házak. Budapest, Ifjúsági és Sportminisztérium. 100. p.

- Székely Levente (2013): Magyar Ifjúság 2012 Tanulmánykötet. Budapest, Magyar Közlöny Lap- és Könyvkiadó. 356. p.

On-line sources:

- https://www.ksh.hu/interaktiv/korfak/orszag.html

- https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=99700140.tv

- https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=99200150.kor

- https://mjcpaysdebegard.pagesperso-orange.fr/

- http://aycc.com.au/

- http://youthcentrescanada.com/

- https://www.foroige.ie/our-work/projects-services-and-programmes/youth-cafes

- https://www.youthfirst.org.uk/

List of the figures:

- Figure 1.: Population of Hungary, classed up to genders and ages

- Figure 2.: Number of communities attended / participant in the research

- Figure 3. Frequency of attendance (Youth community places)